by Jason Biundo (WR/CB, Patriots Wheelchair Football)

Life can change in seconds. For years, I wore a Boston Strong wristband as a reminder of this truth. I was 14 years old when the Boston Marathon Bombing occurred, and I remember being struck that something so terrible could happen just a few miles away from where I was that day. Thousands of people’s lives were forever altered because of one tragic event—and before then I never thought something like that could happen to me.

I was a junior at UMass Amherst when I was injured, immersed in the world of neuroscience and biology. Fascinated by the brain, I had lofty goals of figuring out what goes wrong after nervous system injury or disease, and making research a career meant eventually getting a PhD.

I had just finished a successful summer research program in computational neuroscience at Carnegie Mellon University and returned to UMass in the fall of 2019. I went rock climbing with my friends at the local Central Rock Gym, as I had hundreds of times before, but as I was just about to hit the top of the wall, my hand slipped. I expected the rope to catch me as usual, but it didn’t. I plummeted about 40 feet directly onto my back and was instantly paralyzed below the waist. On the way to the hospital, all I could think about was my physics homework and how I didn’t know how I would complete it!

The doctors in the emergency room said I would never walk again, and after an emergency surgery, the neurosurgeon’s prognosis was similar– I had suffered a permanent, severe spinal cord injury. Initially, I was devastated. But as I recovered in the ICU after my surgery, I realized I was actually quite lucky. I hadn’t injured my head in the fall, and I still had full control of my upper body. The wheels started turning in my head, and I was already trying to figure out how to make this work as I desperately wanted to get back to school.

Soon, I was transferred to Spaulding Rehab in Boston and my recovery journey officially began. I learned quickly that a spinal cord injury is a daily lesson in adaptability. The grueling recovery process included relearning everything from simply sitting up to getting dressed to eventually moving my legs again. At the same time, I became fascinated by the injury itself and was constantly asking my doctors and physical therapists questions about everything from the mechanism of action of the medications I was taking to the biology and anatomy of the spinal cord. My hospital bed had become my first personal laboratory. Ironically, I remember sitting in my neuroscience classes before my injury and being bored learning about the spinal cord. I thought “Why study the spinal cord when the brain controls everything?” Not only was that wrong, I regretted not learning more about the spinal cord for sure!

Despite my injury, I remained a full time student. I completed coursework from my hospital bed and found online resources to strengthen skills that would allow me to excel in a research career from a wheelchair. But despite continuing my classes and amazing support from my friends and family, I still felt like I was missing out. I missed being on campus and around my friends. And while Spaulding had excellent peer mentors, I couldn’t find anyone around my age that could truly relate to what I was going through.

Once I started getting more function back and learned to move around with my injury, an amazing recreational therapist at Spaulding, Ashley, introduced me to adaptive sports. At first, I was hesitant – I had played sports recreationally my whole life and I knew it could be frustrating to have to play in a different way. But after my discharge, I started playing wheelchair basketball with Spaulding’s adaptive sports program. It was there I met Alex, the first young person I’d connected with who also had a spinal cord injury, and he would later become my teammate! I was hooked instantly. I played weekly and began applying for grants to get my own sports chair.

Then in March of 2020, COVID hit and the world shut down. All the local adaptive sports programs were cancelled, with no word about when they would return. I was devastated, but did my best to continue my recovery from home. Eventually, I was able to get back to physical therapy in person but the adaptive sports programs were slow to restart. At that point, the start of fall semester was approaching and after months of isolation, I made the difficult decision to stop my rehab and went back to school. After a year of intense physical therapy, I returned to campus in Fall 2020 to finish my senior year. It was so good to be back on campus – I got a girlfriend (who is now my fiancée!), reconnected with friends, and was able to get back in the research lab. I managed to graduate on time with Magna Cum Laude Honors and two bachelor’s degrees in Biology and Neuroscience.

Still, I desperately missed the community and competition of adaptive sports. So when I graduated and moved back home to the Boston area, I started seeking out adaptive sports opportunities. Eventually, I was connected with Joe LeMar who said a group practices Basketball in Rhode Island twice a week. The drive was long (an hour and a half each way with traffic) but it was worth every minute. The team immediately welcomed me, gave me a chair to use, and showed me how to play wheelchair basketball at a high level.

The first time I rolled into that gym, I was in awe. I had never seen so many people in wheelchairs in one place. Everyone had a different injury, a different story, and a unique way of adapting. I watched Omar, a 30-year veteran of the sport, move his chair in ways I didn’t think were possible, balancing on one wheel to grab a rebound. I saw players collide, fall out of their chairs, and hop right back in without missing a beat. I wanted to move like that! As a scientist, I’m trained to observe and ask questions, and I became a sponge. They answered every question, and soon, I felt like I could keep up.

One night at one of the basketball practices, as we were warming up I had a discussion with some of my teammates who expressed some concern about getting the COVID vaccine. I did my best to explain that it was both safe and effective, but when I wasn’t quite getting through I remember blurting out something like “I’m a scientist! I can tell you how it works and I promise it’s safe.” The rest of the practice, my teammates would yell “science!” or “professor!” before passing me the ball or after a good play. The nickname stuck, and now most people just call me “Science.” I don’t even think some of my teammates know my real name at this point!

I love the nickname. It’s a perfect blend of who I am- a scientist athlete.

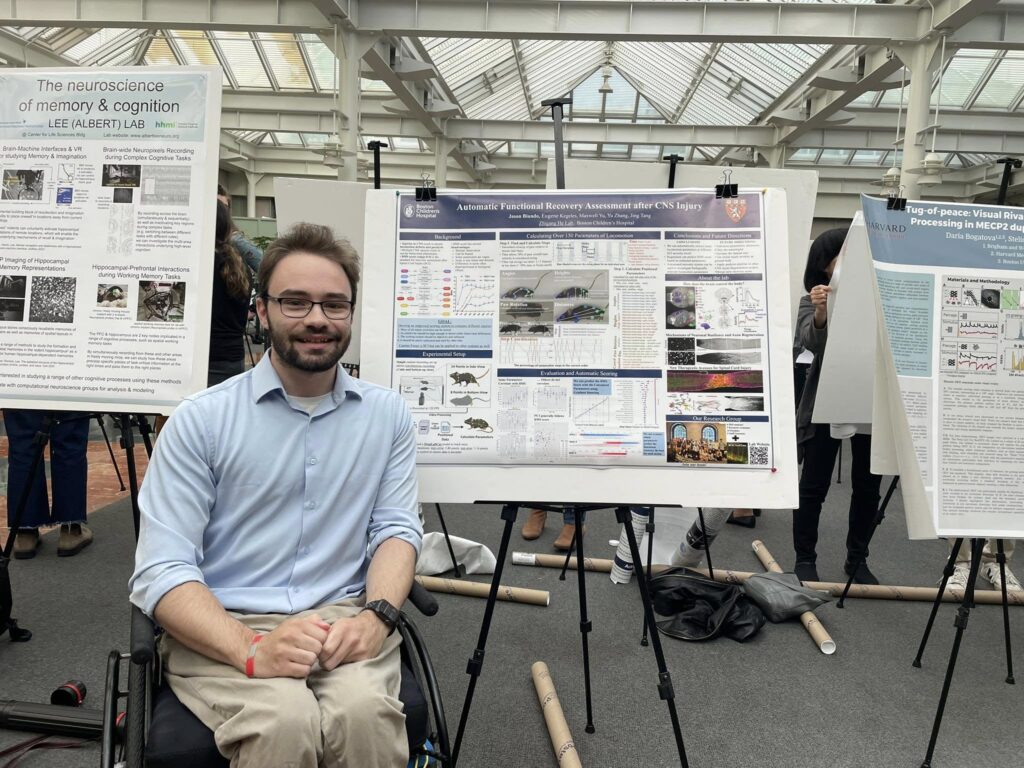

At the same time as I started playing adaptive sports, I started working at Boston Children’s Hospital doing spinal cord injury research. I joined one of the best labs in the world to try and use my own personal experience with the injury and turn it into meaningful therapies. Our lab studies ways to regenerate injured nerves after spinal cord injury and also why the spinal cord has such a hard time repairing itself in the first place. My personal experience isn’t just motivation; it’s a tool. It allows me to investigate research questions that others might overlook and helps bridge the gap between researchers and the SCI community we aim to serve. I live the problems we are trying to solve.

As I got closer and closer with the group from Rhode Island playing basketball, a new opportunity came up – a wheelchair football clinic at Gillette Stadium hosted by Adaptive Sports New England and The Patriots Foundation. I have always loved football and the Patriots (how could I not when they were so good?!), so an opportunity to play Wheelchair Football sounded incredible! All of my teammates from basketball came to the clinic, and we had an amazing time. We practiced chair skills, threw footballs around with volunteers from the Renegades Women’s Football team, and played in a scrimmage. I remember being surprised how physical it was and how much contact there was between the chairs – I like to describe it to others as football bumper-cars! From my first touchdown in that scrimmage I was immediately hooked.

Soon after, we started having regular practices and tryouts for the team. We formed a team, and I found myself applying the same analytical mindset from the lab to the field. We experimented to find the best positions for everyone, analyzing our functional strengths and weaknesses. My speed and ability to catch made me a natural fit for wide receiver and cornerback.

One of my favorite parts of working in a lab is applying the topics and concepts I learned about in class to experiments: when I do something in the lab that I had only previously read about in textbooks or research papers, the concepts come together in my mind, and I find myself learning a lot more. I bring that same approach to the football field. While I had never played organized football growing up, I’ve followed it closely my whole life and as we ran plays and learned about different kinds of defenses, my understanding and appreciation for the game increased exponentially.

When we were finally ready to travel to our first ever tournament, I unfortunately had to sit out for medical reasons. One of the more unknown but highly impactful side effects of a spinal cord injury is an increased risk of skin breakdown due to loss of sensation and reduced blood flow. I had developed a bad skin issue and it just wasn’t safe for me to travel or play. I was disappointed to miss out, but it only made me want to practice harder the next year.

The next season, I was dying to get started. We kept our twice-weekly practices, and the team leveled up: our communication was tighter, our spacing smarter, and timing sharper. Then a hurricane canceled the Tampa Bay tournament we’d been eyeing the night before we flew out. Another gut punch.

Chicago was next, scheduled the weekend before I started graduate school at Harvard Medical School. I almost stayed home to play it safe. But after missing so much, I couldn’t let another opportunity slip by. I went and it was one of the best experiences of my life. Once we shook off our nerves, we played with heart. We discovered an amazing camaraderie, not just within our team but with teams from across the country. Playing in the tournaments is fun, but some of my favorite parts of the tournaments are the moments between or after games where we have time to sit as a team and just chat about life. We share our stories and experiences, commiserate on the struggles we face, and laugh until we cry!

This year, after an unforgettable summer of intense practices, we travelled to Tampa (we made it this time!) and had another great tournament. Even though we didn’t win all of the games, we had great moments and the future of the team is looking bright. Our team is growing with a strong set of new players, and with each practice and game we’re getting better. We’re hoping to take the lessons we learned from this tournament into our next tournament in Kansas City in a few weeks!

On paper, my roles might look separate: graduate student, researcher, wide receiver, cornerback. In reality, they’re fused. Research makes me a better athlete: more analytical, more adaptable, more relentless about small improvements. Sport makes me a better scientist: more grounded, more collaborative, more aware of the lived realities behind every data point. And my injury ties it all together, not as a limitation but as a way of seeing problems clearly and moving toward solutions.

Back when I first wore the “Boston Strong” wristband, I understood resilience as something to admire from afar. After my injury, my family made “Jason Strong” wristbands. They became our reminder that we can adapt, we can grow, and we can find strength not in spite of our challenges, but because of them. I still wear one. It reminds me that life can change in seconds, but what defines us is how we respond.

Today, when I roll onto the field with the New England Patriots Wheelchair Football Team, I bring the lab with me: data, and the drive to iterate and keep improving. And I also bring my team back to the lab with our stories, and the urgent need to make research matter. I’m proud to be called Science on game day, and I’m even prouder to be one of many adaptive athletes proving, play after play, that adaptation and resilience only make us stronger.

Comments are closed